By definition, comprehension is a process of active engagement that leads to an accurate understanding and interpretation of what is read. It is a dance between the reader and the text involving thinking and reasoning. To be able to comprehend text, students must be able to decode words and understand the meaning of those words.

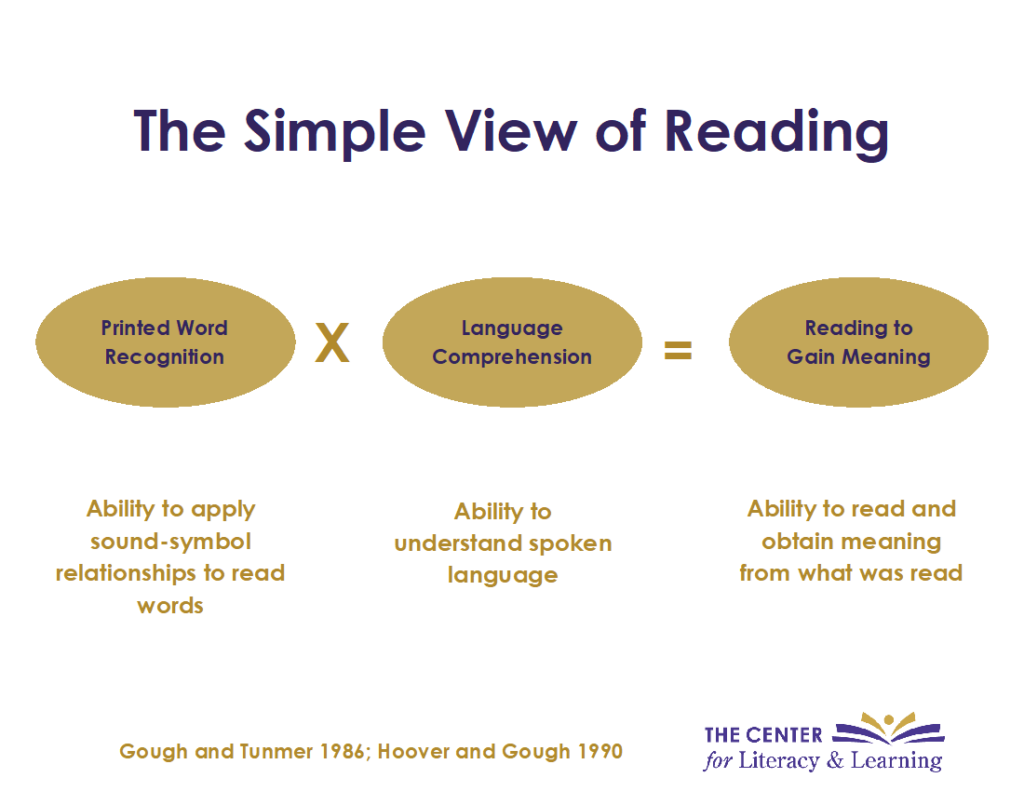

This “Simple View of Reading” is represented in Gough & Tunmer’s equation, showing that students need both decoding and oral comprehension skills to have effective reading comprehension. Comprehension is the overarching goal of reading.

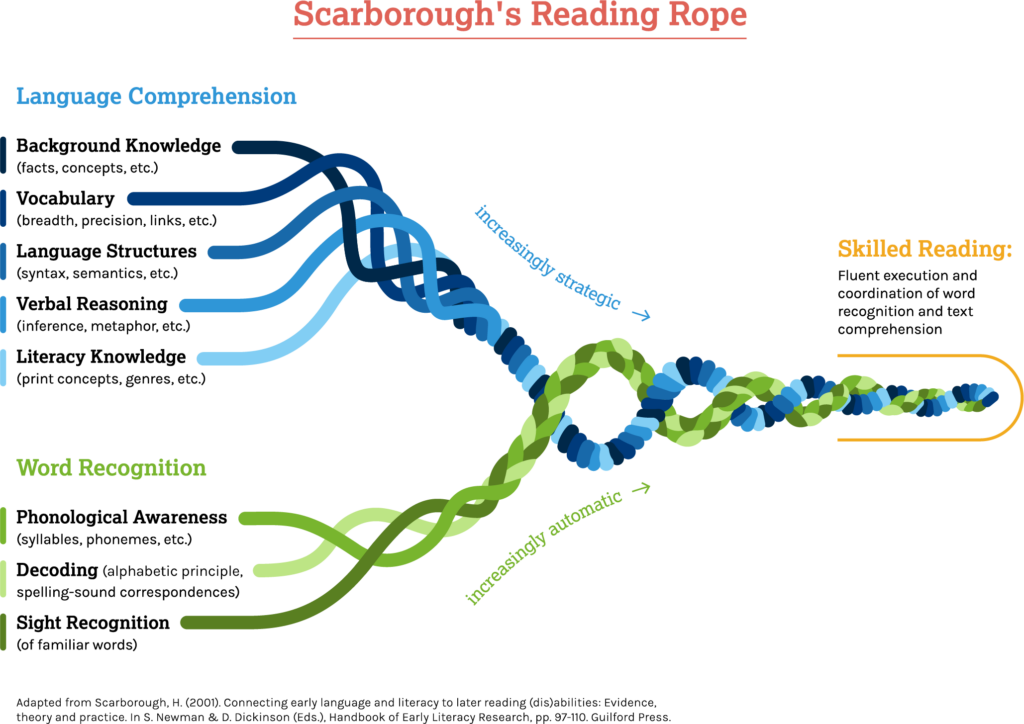

This visual representation is further extricated in Scarborough’s Rope. It reminds us that reading comprehension is a complex behavior and relies on the orchestration of many strands of linguistic and cognitive processes necessary for skilled reading.

In addition to building a solid foundation in decoding and word recognition skills, there are other strategies that good readers use to monitor their reading and ensure that they understand what they are reading. These strategies allow readers to process text, extract meaning, and connect ideas in ways that make reading an enjoyable quest for knowledge, ideas, and information about virtually everything and anything!

Strategies that Enhance Comprehension

Visualizing

Reading fuels expansive imagery that carries the reader on a journey of learning, thinking, and experiencing the world. The sheer act of reading unleashes mental images that allow information to impact the senses and builds a “mind movie” that keeps the reader coming back for more. One good poem, story, or novel, and we are hooked! Unfortunately, not all students can experience the magic in written words or the power that reading has when it unlocks the imagination.

Various strategies can be incorporated to stimulate the visualizing process during classroom reading. Teachers should not be worried about “interrupting” reading. Modeling these strategies and taking time to focus on the thinking side of reading will enrich imagery and comprehension.

Try it:

- Weave sensory-related questions throughout reading (What do you see/feel?)

- Allow students to draw their images of the characters, setting, and event details

- Share your own sensory images while reading to students

Look for evidence that students are comprehending the text. When comprehension is active, students will:

- ask to keep reading,

- laugh at appropriate times,

- stop to ask good questions,

- offer details,

- read with expression, and

- make sound predictions along the way.

Background Knowledge

Knowledge and comprehension are partners in reading. When students have experiences that enhance their knowledge about a broad range of topics, the text becomes easier to read, understand, and remember. These experiences may include family engagement, travel, multimedia exposure and early introductions to books and reading. These opportunities vary from child to child and compile the background knowledge essential for reading comprehension. Understanding what students know before reading begins can provide teachers will valuable assessment information. Teachers can introduce pre-reading strategies to boost students’ schema when background knowledge is limited. Schema encompasses everything a reader brings to the text, all of their experiences, images, and memories about a subject. The use of graphic organizers is beneficial when modeling and building schema. Teachers can solicit ideas in the classroom and jot them on a thinking map, have students contribute to a K-W-L chart, or encourage information sharing with a turn-and-talk activity. When teachers recognize that schema needs to be activated prior to reading, they can select supplemental material such as images or videos, historical documents, storytelling, field trips, anticipatory guides, or virtual simulations to prime the student for reading. Building background knowledge can also positively affect other skills like inferencing, questioning, and summarizing.

Vocabulary

While research continues to investigate best practices for teaching vocabulary, numerous findings confirm the importance of word knowledge to the success of reading. Two types of vocabulary are necessary to generate comprehension. Print vocabulary refers to words the student can read or decode. Oral vocabulary refers to words the student understands when spoken. So, it is not enough to be able to read the word, the student must also know the word’s meaning to generate an image in the context of the text. Researchers will agree that mental imagery is enhanced when the student has both a depth (extent) and breadth (broad range) of vocabulary knowledge.

Teachers will want to take advantage of many opportunities to teach new vocabulary across speaking, reading, and writing activities, including direct instruction, incidental teaching, and computer programs.

Text selection matters. Teachers will want to be intentional in their choice of reading selections. The best text provides an array of rich, sophisticated vocabulary, complex sentence structure, varied discourse, related academic language, and plenty of opportunities to mentor grammar instruction.

Read-alouds are a necessary instructional opportunity to ignite the students’ love for reading while providing language experiences that focus on individual words, word-learning strategies, and word consciousness. Other key instructional practices for vocabulary development can be found in the previous article on Vocabulary.

The grammatical and structural basis of written language can lead to a breakdown in comprehension. Weave grammar instruction into reading opportunities and engage in deconstruction activities using mentor text from read-alouds to demonstrate how words work together. Understanding how the parts of speech, phrases, clauses, and syntax affect our reading will lead to improved comprehension.

Metacognition

Metacognition is the process of thinking about how we think and learn. Often referred to as “thinking about thinking”, it is essentially exercise for the brain. In addition to helping the reader make connections to self, other text, and the world, metacognition allows for the reader to plan, monitor, and activate strategies when new information is presented. The engagement between our thinking, reflecting, and verbalizing leads to a deeper understanding of the text. Through the think-aloud process, the reader examines the mental images that are directly connected to life experiences, background knowledge, and memories. Teachers need to be intentional when providing students with “process time” to be able to read, talk, write, and think. Research indicates that good readers take time to think.

Teachers can facilitate modeling and questioning by explaining their own thinking processes. This practice is especially helpful when tasks involve planning multiple steps, selecting the right strategy, or a problem is encountered. For example, a teacher may model metacognitive thinking by making the process of checking for understanding visuals to the students. During a read-aloud, teachers should verbalize examples of their thoughts, “This part is a little fuzzy for me, so I am going to reread this part and then try to visualize what is happening before I read on.”

In addition to modeling the process, teachers promote growth mindset, reminding students that experiencing confusion and mistakes is an inevitable and acceptable part of learning.

When teachers focus on metacognition in the classroom, they create a culture of thinking that increases students’ flexibility, productivity, and overall independence. When practiced as an integral part of learning, metacognitive strategies can have a profound and pervasive effect on a student’s self awareness-leading to improved comprehension.

Questions

Questions help the reader clarify ideas while they deepen our understanding of the text. Research indicates that good readers pose questions before, during, and after reading.

Their minds are full of wonder and their questions are the outcome of active cognitive engagement. Teachers should model questioning right from the start.

Calling students’ attention to the cover of a book while asking, “What do you think this book will be about?” prompts predictions and inquisitive curiosity. The classroom is rich with reading opportunities, so pre-planning guiding questions will foster inquiry, heighten understanding, and ensure a transfer of learning.

Teaching students to ask the right questions can make a big difference. QAR (Question-Answer-Relationship) is a strategy that improves comprehension by teaching students that the answers to some questions can be found “right there” in the text, while others require the reader to “think and search”. Being able to find a keyword or words within a question can assist students in scanning a passage more effectively and efficiently. Often, the keyword in the question is a clue that matches a word or words within the text, making it easier for students to hone in on answers.

The use of this strategy will promote self-monitoring when used during and after reading. The QAR strategy can be taught and modeled within whole group lessons to boost comprehension and test-taking skills.

Students can write after-reading questions on an exit ticket at the end of the day or before class lets out. Using the students’ lingering questions is an excellent segway to summarize the end of a chapter and will prompt new predictions for the text to come.

Activities to Extend Comprehension Beyond the Classroom

Modeling and teaching students about comprehension in the classroom is vital to reading success. However, there are ways to keep students thinking, activating, and sharing their strategy-use outside of class.

The Fab Four

Reciprocal Teaching is a comprehension strategy that involves and engages students in the reading experience. Through a gradual release approach, students are exposed to the four building blocks of comprehension: predicting, questioning, clarifying, and summarizing. Lesson plans are easy to implement in small or whole group and can be modified for different grades.

Sketch Poetry

This activity allows students to demonstrate their interpretation and understanding of an author’s use of descriptive and figurative language by drawing a picture that shows their mental image of a poem or short story.

Students can compare and contrast their sketches in small or whole class discussion.

Family Book Club

Teachers can assign a grade-appropriate book to be read at home with family members. Encourage all participating family members to journal their thoughts, wonders, and questions in a notebook as they read. Students can share their experiences and collective metacognitive processes with each other.

Brainstorming Kits

Create in-class or take-home kits that give students access to the various materials that support the use of comprehension strategies. Model how-to use sticky notes for brainstorming, note-taking, and thought jots. Include highlighters for annotation and ah-ha moments during writing. Students love a collection of miniature notebooks and notepads that can be used in the same way that a good detective gathers clues or a journalist notes important thoughts and observations to reflect on at a later time.

Author It

Keep a selection of wordless books around for students to practice being the author. Wordless picture books allow students of all ages to build comprehension while combining illustrations with their imagination and background information.

Without text, students must activate inferencing skills to understand the story structure and plot. Activities using wordless books can also provide practice that enhances language, vocabulary usage, fluency, grammar, and application of punctuation.

Dialogic Reading

Provide educational resources to caregivers to introduce effective discussion prompts that will encourage students to think about text on a deeper level.

This is a great way to share the reading journey and encourage a love for reading during the early years.

Resources for Teachers

- The Reading Comprehension Blueprint by Nancy Hennessy

- Reciprocal Teaching at Work: Powerful Strategies and Lessons for Improving Reading Comprehension by Lori Oczkus

- Find a list of the 30 Best Wordless Picture Books at https://imaginationsoup.net

- Find downloadable handouts in many languages about Dialogic Reading at https://www.readingrockets.org

Check out the rest of the series:

- The Essential Components of Literacy Instruction, Part 1 of 6

- What Is Phonological Awareness? Part 2 of The Essential Components of Literacy

- What Is Phonics? Part 3 of the Essential Components of Literacy

- What Is Vocabulary? Part 5 of The Essential Components of Literacy

- What Is Comprehension? Part 6 of The Essential Components of Literacy

Please connect with us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn, and Pinterest to get tips and tricks from your peers and us. Read the IMSE Journal to hear success stories from other schools and districts, and be sure to check out our digital resources for refreshers and tips.