One might not expect a gym or art teacher to need to know how to teach children to read, but at least one Colorado school district who offered free literacy training to its entire staff found the program has resulted in an amazing improvement among its students — especially those struggling with learning issues like dyslexia.

Teachers at Bergen Meadows and Bergen Valley Schools, a set of top-rated pre-K-5 buildings in the mountain town of Evergreen, Colo. just 30 miles outside Denver, have been taught a technique called the Orton-Gillingam method by the Institute for Multi-Sensory Education, a Michigan-based literacy training company that has helped turn around some of the country’s largest school districts.

Orton-Gillingham (OG) is a long-used, research-based style of reading instruction that was traditionally used to help children with Dyslexia and other learning differences read, with incredible documented success. The technique uses multi-sensory methods, like physical movement, games, auditory and oral drills, repetition and more to engage students across the learning spectrum in learning to read and write.

Once thought only to help struggling readers, research now shows that Orton-Gillingham instruction can help all students realize new and advanced reading potentials, while also helping to better prepare new teachers.

“OG is really a program that supports students with dyslexia, however, it’s just good instruction that’s good for all kids,” said Principal of both schools Peggy Miller. “When you look at any kind of intervention or any kind of program, you’re always looking for the lowest common denominator, you’re thinking of the kids that are struggling. And we said, this is good instruction for all kids. Our school is really high-performing, and there’s always room for growth.”

“This is good for all kids, and we’re going to do it for all kids.”

Peggy Miller is the principal of Bergen Valley and Bergen Meadow schools in Evergreen, and said IMSE’s OG has been instrumental to bolstering literacy at the schools.

IMSE’s OG is a program that – at first – the state’s No. 1 top-rated private school didn’t know it needed, Miller said. Her students were already testing high, but, like all states, Miller knew students in Colorado were struggling with literacy. She wanted to find out specifically where she could help her own flock.

“We’d seen a rise in dyslexia in our community,” Miller said. “But really I’m not sure if it’s a rise in dyslexia, or it’s a rise in parents being savvy and knowing what that looks like. And [the parents] really wanted everything [available] for the kids to be successful.”

A recent “State of Literacy in Colorado 2017” report by Stand For Children, an education advocacy nonprofit, found that Colorado’s most recent National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) test scores revealed that less than 40 percent of the state’s fourth-graders were proficient in reading and literacy skills, and about 10 percent of adults in Colorado also “lack the most basic literacy skills.”

That same report found that of Colorado students who graduated during the 2015-16 school year, over 36 percent required college remediation, resulting in “tremendous costs to the state and students” — upwards of $70 million during the 2015-16 and 2014-15 school years alone.

So, as awareness around literacy rates and dyslexia was rising in Colorado, Miller said her school began to take a deep dive into their data to see where improvements could be made. The research caused a realization: students were having trouble spelling.

“We kept digging and digging and were like, ‘Oh my gosh, our kids can’t spell,’” Miller said. “And if they can’t spell, they can’t transfer it. We knew this was going to be a problem for them down the road.”

“So we just kept digging deeper and we looked at phonics [and wondered], ‘What are we teaching? Are we teaching them the rules? Do they still know the rules by fifth grade? Do the teachers even know the rules?’”

The need for better literacy teaching tools at the Bergen Schools hit even harder when a new school opened across the street, specifically geared toward supporting students with dyslexia and other learning disabilities. Miller said they did see some of their students switch schools.

In August of the 2016-17 school year, Miller sent six of her teachers to an Orton-Gillingham training given by the Institute for Multi-Sensory Education. By the end of the school year, every K-5 teacher had taken the training.

“They came back just on fire,” Miller said. “They explained everything to the rest of the teachers throughout the year, showed them the results, talked to them about the systemic piece, the strategies for everyday, the lesson piece, just talked about everything they learned, so our teachers said, ‘Yeah, let’s do it.’”

Seeing the immediate success IMSE’s Orton-Gillingham technique was bringing to the classroom, for the 2017-18 school year, Miller said she decided to send all of her staff for OG courses, including 24 classroom teachers, art, gym and music teachers, two special education teachers and an interventionist.

“We learned a lot,” she said. “Intermediate teachers had forgotten how kids learned to read, so that was eye-opening.”

Bergen Meadows School in Evergreen, Co.

After she sent some of her intermediate teachers, who work with older students, to the Intermediate-level OG training, she said they came back feeling refreshed and more knowledgeable than ever.

“They said, ‘I get it now, I understand,’” she said. “So we’re going to send more teachers to the Intermediate training.”

Overall, the work has paid off with “amazing results” for her schools, Miller said.

During the spring semester Miller said she has been observing OG use in every classroom.

“What I noticed is: Kids know the routine and kids like it. When they talk about [sight] words, kids always remember them,” she said.

She also personally tested second graders who weren’t meeting benchmarks on their nonsense word fluency — once in the fall and then again in January.

“They all improved unbelievably, it was amazing,” Miller said.

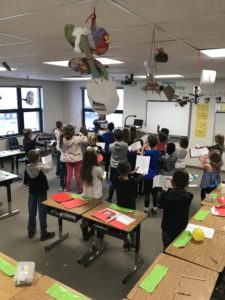

Third-grade teacher Elizabeth Mehmen’s class arm-tapping together.

Third grade teacher Elizabeth Mehmen received OG training from IMSE in August 2017, and, with the information fresh in her mind, began applying the knowledge she learned in her classroom right away, she said. Though she was already using a literacy program, Mehmen said her general education students, which also included ESL and students with learning disabilities, needed something deeper and more explicit.

Her students struggled with things like vowel combinations, words ending in “-y,” and recognizing the difference between “ch” and “ck.”

“My teaching has to be very direct and explicit; it has to be a lot of repeating and a lot of drills and just broken down to every minute detail — which OG gives me,” Mehmen said.

Using OG’s multi-sensory tactics, Mehmen now incorporates fun and silliness into her lessons, like using different voices and calisthenic movements to accompany sound cards.

So far, it’s made a monumental difference, she said.

Not only are her students more engaged and gaining a love of reading, they’re feeling more inspired and empowered than ever.

“Every Wednesday, a different child teaches the [sight] words, so it’s like a gradual [build-up],” she said. “By Thursday when we’re doing more practice … I have another child be the teacher, so a lot of it has become shared in the classroom, which is super fun and it adds to their engagement. It’s been fantastic.”

“It’s hilarious, they could teach the drill cards, they don’t even need me,” Mehmen said with a laugh. “It makes them excited, there’s huge ownership. Having them take over some of that lesson has been huge.”

The Bergen Schools aren’t the only Colorado schools using Orton-Gillingham training from IMSE either: teachers in Colorado Springs District 11’s 36 elementary schools are using it to help them comply with the state’s reading requirements as well — and also with success.

“We know that our elementary teachers are coming in not as prepared as we’d like them to be out of college,” said D-11’s Elementary Reading Specialist Christy Feldman. “[Teachers] learn so much, and they’re so excited to have it. They like the materials, they have loved the trainers that we have had; we have been very successful with it.”

Looking forward, Bergen teachers like Mehem said she’s excited to finally have a teaching tool in her repertoire that will have high-impact on her classroom, particularly because it improves learning for all of her students, not just some.

“Nothing in the English language is intuitive, so I absolutely would recommend we continue using Orton-Gillingham,” Mehmen said. “They love it, they absolutely love it.”