“Reading and writing have been thought of as opposites – with reading regarded as receptive and writing regarded as productive. Researchers have found that reading and writing are ‘essentially the same process of meaning construction’ and that readers and writers share a surprising number of characteristics” (Carol Booth Olson, 2003).

Therefore, the explicit instruction of encoding and decoding strategies support progress toward mastery, which is the ability to read, write, and spell as one body.

Is Explicit Reading & Writing Instruction Necessary?

While oral language is a more natural human development process, written language (including reading and writing) must be taught.

Learning to read, write, and spell may be challenging for students, and seeking opportunities for incremental success through explicit, sequential, multisensory instruction proves incredibly motivating. This is especially true for English language learners and individuals with diagnosed learning disabilities such as dyslexia and dysgraphia.

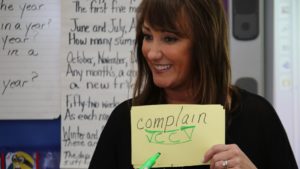

IMSE Co-Founder Jeanne Jeup.

When learning something is difficult, it’s easier to dismiss it entirely. “Is this really necessary?” or “I can make it without knowing bigger words because I already know a basic word which means the same thing.”

So why is it important to continue the literacy journey? Why should I read? How will learning these [new phonetic concepts or strategies] help me in the long run? There are many reasons why reading, writing, and spelling are important.

What Is Encoding?

Spelling is critically important when completing job applications, establishing credibility as a writer, using a literal or online dictionary, or recognizing the best choice when using spell check (Liuzzo, 2020).

According to Marcia Henry (Unlocking Literacy, 2004), to be an accurate reader and speller, one must know of:

- Phonology: the study of sounds

- Orthography: the study of writing systems and sound-letter correspondences

- Morphology: the study of word parts that shape word meaning

- Etymology: the study of the history of words

According to Peter Bowers (2009), “Explicit instruction about the role of phonology and etymology is not optional if we accept the challenge of offering students accurate, comprehensive instruction.”

Encoding is the process of breaking a spoken word into each of its individual sounds, known as phonemes. Phonemes are the smallest units in our spoken language that distinguish one word from another.

“The development of automatic word recognition depends on intact, proficient phoneme awareness, knowledge of sound-symbol (phoneme-grapheme) correspondences, recognition of print patterns such as recurring letter sequences and syllable spellings, and recognition of meaningful parts of words (morphemes)” (Moats, 2020) and (Ehri, 2014).

Knowledge of spelling patterns and rules knit together the layers of the English language as students use phonology, orthography, and morphology to identify how to spell words. For example, understanding why suffix -ed makes each of its three sounds, /id/, /d/, or /t/, hinges on identifying the final sound of the base word. Students must first hear the past tense verb and isolate the base word.

In the past tense verb asked, the base word is ask which ends in unvoiced sound /k/. Therefore, in the past tense verb asked, the suffix -ed will make its unvoiced sound /t/. As the student encodes the word, they must apply their knowledge, as, “I hear /t/, but I write -ed.” Ensuring mastery of phonological awareness skills as a foundation upon which students build phonetic knowledge is extremely important.

Students will segment to spell the phonemes in monosyllabic and polysyllabic words with increasing automaticity. Thus, a fluent writer is born.

Be sure to check out the rest of our blog series on Encoding vs. Decoding:

- Decoding Part 2 of Encoding vs. Decoding

- Irregular Words Part 3 of Encoding vs. Decoding

- What Should We Read? Part 4 of Encoding vs. Decoding

Please connect with us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn, and Pinterest to get tips and tricks from your peers and us. Read the IMSE Journal to hear success stories from other schools and districts, and be sure to check out our digital resources for refreshers and tips.

About The Author

Ginny Simank is a Level 4 IMSE OG Master Instructor living in Dallas, Texas. She has a master’s degree (M.Ed.) with a Reading Specialist certificate and holds certifications in special education, English as a Second Language, and generalists for Early Childhood through 6th grade & ELA 4th-8th grades. She is an IDA-certified Structured Literacy Teacher and full-time instructor for the Institute for Multi-Sensory Education (IMSE), whose mission is to train others across the country (teachers, administrators, tutors, education professionals & parents) in the Orton Gillingham methodology of multi-sensory language instruction. Ms. Simank previously served on the national board of directors for the Learning Disabilities Association and was a member of the LDA’s Education & Nominating Committees.

Sources

- Bowers, Peter (2009). Teaching How the Written Word Works. www.wordworkskingston.com.

- Ehri, L. “Orthographic Mapping in the Acquisition of Sight Word Reading, Spelling Memory, and Vocabulary Learning,” Scientific Studies of Reading 18 (2014): 5–21; and Kilpatrick, Essentials of Assessing.

- Ehri, L., et al., “Systematic Phonics Instruction Helps Students Learn to Read: Evidence from the National Reading Panel’s Meta-Analysis,” Review of Educational Research 71 (2001): 393–447.

- Gallagher, K. (2003). Reading Reasons: Motivational Mini-Lessons for Middle School and High School. Portland, ME: Steinhouse Publishers.

- Henry, Marcia (2004). Unlocking Literacy, Paul H. Brookes Publishing Company, Second Printing.

- Liuzzo, Jeanne (2020). Intermediate Training Manual, Institute for Multi-Sensory Education, p53-56.

- Moats, Louisa C. (2020). Teaching Reading Is Rocket Science (2020): What Expert Teachers of Reading Should Know and Be Able to Do. Washington, DC: American Federation of Teachers.

- Olson, Carol Booth. 2003. The Reading/Writing Connection: Strategies for Teaching and Learning in the Secondary Classroom. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Sign up for our LIVE virtual Orton-Gillingham training! We are now offering half-day, evening, and weekend options to best fit your schedule.

The IMSE approach allows teachers to incorporate the five components essential to an effective reading program into their daily lessons: phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension.

The approach is based on the Orton-Gillingham methodology and focuses on explicit, direct instruction that is sequential, structured, and multi-sensory.

It is IMSE’s mission that all children must have the ability to read to fully realize their potential. We are committed to providing teachers with the knowledge and tools to prepare future minds.