A 1979 study by University of Chicago professor Nancy Mavrogenes argued that students from poor backgrounds can improve their vocabularies by studying Latin. And a 1981 paper by University of Georgia classics professor Richard LaFleur found that knowledge of Latin improved SAT scores in both the language and math sections of the test. That having some Latin would also improve your math score may be counterintuitive, but as LeFleur put it, Latin helps boost, “ordered thinking.”

Numerous other studies conducted over the years have shown that reading proficiency is directly linked to the expanse of a student’s vocabulary.

Simply put: bigger vocabularies lead to better readers.

“…upwards of ninety percent of our academic words in English…are derived from Latin and Greek.” – Professor Tim Rasinski, Kent State University

That’s why more and more educators today are introducing early readers—as early as first grade, in some cases—to the Latin and Greek bases within English words. With these tools, students can more quickly expand their vocabularies, better make connections between words and even use these bases as a bridge to other languages like Spanish.

By training students to recognize these patterns early on, teachers are helping them to unlock other related words and building their overall English vocabulary, as well as building a bridge to other Latin-based languages. Understanding that ‘nationem’ in Latin relates to ‘nation’ in English helps ELLs—English language learners—make a direct connection back to their native Spanish word, ‘nacion.’ ‘Nation’ and ‘nacion’ are cognates, words that share the same root and are pronounced and spelled nearly the same way. Understanding the common base <nate> meaning “born or birth,” along with the suffix <ion> meaning “act of”, will help unlock further understanding and comprehension of text.

Tim Rasinski, professor in the Reading-Writing Center at Kent State University, explains that by exposing children to the concept of Latin and Greek bases, teachers are helping to unlock their innate skills in recognizing patterns and creating a solid organizing principle around which students can begin building stellar vocabularies.

Parents and teachers have long understood the power of phonics for young readers—in more technical terms: ‘phonemic’ and ‘phonological’ awareness builds on children’s understanding of the individual sounds in words and the ability to manipulate them and larger units of sounds, including syllables.

Morphological awareness is also a key part of student development. A ‘morpheme,’ is the smallest meaningful unit of language, that cannot be further subdivided.

In 2011, educator Helen Finley was a Title 1 reading specialist in Southwest Missouri. She participated in an IMSE seminar on morphology hosted by educators Gina Cooke and Pete Bowers. (More on Gina’s work at her web site: http://linguisteducatorexchange.com/about/; Pete’s web site: http://www.wordworkskingston.com/WordWorks/Home.html)

“I had been a teacher for twenty years, so I was aware of the concept of morphology. But, for me, it all really came together in that seminar. In the classroom, I would start on Mondays with a ‘morpheme chart,’ to cover our base word and throughout the week, students would keep an eye out for other words that contained that base word,” Helen says.

“It was amazing to me how easily, by the end of the week on Friday, students were picking up new words to add to their repertoire,” Helen recalls. “I felt that they were forming a much deeper understanding of words along the way.”

By training students to recognize these patterns early on, they are both unlocking other related words and building their overall English vocabulary, but also building a bridge to other Latin-based languages. Understanding that ‘nationem,’ in Latin relates to ‘nation,’ in English helps ELLs—English language learners—make a direct connection back to their native Spanish word, ‘nacion.’

As the largest growing student population in the country, ELL students can benefit from an emphasis on Latin bases, while native English speakers are exposed to interconnectedness of different languages.

“…one of our students noticed that there was a TRI in the word Tripoli and…asked what did it have to do with threes. Tripoli, Libya is a city that began as three cities that moved; that merged into one.” Professor Tim Rasinski, Kent State University

In using this approach, students are also exposed to other subjects like world history, politics and geography. When children are given a leg up on subjects like history and geography well before they’re traditionally taught, they have a better chance for success when they are fully immersed in them later in their schooling.

Introducing these concepts to primary level readers can (and should be) fun. Professor Rasinski and his colleagues suggest that primary teachers begin by focusing on ‘one to two roots per week through 10 minute sessions three to five times per week.’

(To read Professor Rasinski and colleagues’ 2011 paper, “The Latin-Greek Connection,” please visit: http://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ961014)

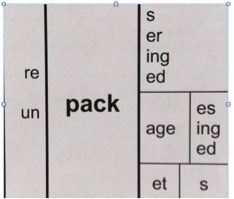

Rasinski also suggests using the ‘divide and conquer,’ approach. This method involves selecting 10 words with the same prefix—such as ‘re’—and examining with students aloud what each word starting with ‘re’ means. ‘Reboot,’ ‘replay,’ rewind,’ are all linked by their prefix and all relate back to their Latin origin meaning of again or back.

“When teachers begin to embrace this approach they’ll be able to say something that Julius Caesar once said when he conquered Gaul…”Veni Vidi Vici, I came, I saw, I conquered.” Professor Tim Rasinski, Kent State University

By creating an interactive environment early, students are transformed from passive learners to word detectives. They are active partners with their educators in seeking out the connections between words and finding their meanings organically. A far more effective approach than handing out lists of words in the later primary grades that must be memorized, regurgitated for a test and then, in many cases, forgotten.

“For me, [as a teacher] it was exciting to watch that ‘light bulb’ moment happen with students when they would make those connections,” Helen says.

And, as she points out, “It is not just about Greek and Latin bases, but it is about looking for structure and meaning in words of any origin. If you see a novel word that has a base that you are familiar with from other words, you have a cue to the meaning of that new word even if you don’t know it.”

The key is embracing morphology as a structured way to guide students through the language.

Introducing Latin and Greek bases in the early primary grades is one way to efficiently jump start students’ vocabularies and help them build bridges to a whole host of other subjects and languages outside of English. Grouping words together by their bases is both efficient and effective.

Beyond early primary school, students in the fifth and sixth grades and middle school might be delighted when they find the appearance of Latin in the massively popular Harry Potter books. That’s because author J.K. Rowling studied Latin as part of her education at Exeter.

The folks behind the venerable Oxford English Dictionary have taken note of Rowling’s use of Latin and Greek in the Potter books, too:

“Petrificus Totalus:a full bodybinding curse. This is another of Rowling’s blends. Although petrificus is not a Latin word, the Greek borrowing petra means rock. The suffix –ficus, which ascribes a sense of making or becoming to its headword, is very common in Latin. In Modern English, this sense of the affix –fic is still present in words like terrific, certificate, or mummification. Totalus is an alteration of Latin totalis ‘total’.” (source: http://blog.oxforddictionaries.com/2013/07/spellsharrypotter/)

In many ways, Latin never really never went away. And educators across the country are again using it as a means of unlocking English for their students and harnessing the power of its words.